The intersection of Can’t Stop and Lamar in San Antonio

I ran across (so to speak) the above intersection while scouting in San Antonio. There must be a great story behind that street name.

Tim Orr and I go up to Toronto on Tuesday to view the answer prints of the film. This will be the first time that either of us will have seen the actual film of EvenHand. Up until now, the entire process has been digital (for the picture editing) or we have used the Beta tapes made from the original negative (for the sound mix & ADR sessions). It’s kind of weird working on a 35mm film for well over a year and never actually seeing the film (or a projection thereof). I don’t expect any big surprises; the conform (Beta tapes edited to match the Avid output) looks really good, so the film should as well. By Wednesday, I expect it will be looking superb as Tim will have a series of mysterious conversations with the color timer and make innumerable subtle changes to the look of each shot (darker, lighter, more cyan, less magenta…). Then, sometime in the near future, after two or three answer prints, we will actually get to see the final print. Outstanding. Now all we need is somewhere to screen it!

The Bills enjoy some quality time with a two-dimensional fashion model.

Speaking of which, here’s a link to the website of our new favorite: ELLONA!!!

Since there is really not much happening here now, and I can only stretch the anticipation of the excitement of the viewing of the answer prints so far (one paragraph, I guess), I’d thought I’d digress and tell the story of my first day on set as a location manager on a feature film.

The film was Five Corners, directed by Tony Bill. It starred a young Jodie Foster (in one of her first adult roles), Tim Robbins and John Turturro. The late Rodney Harvey had a small role, as did Todd Graff (better known these days as a writer). John Patrick Shanley wrote the screenplay. If you have never seen it, please rent it! It’s a terrific film that somehow slipped largely and undeservedly into obscurity.

I had had some experience doing locations on a couple of TV movies and was ready for the jump to a moderately budgeted feature. Pre-production went well, especially after we finally identified the elusive “five corners” neighborhood. It ended up being a small working class area just South of the Triborough Bridge in Astoria, Queens. All my efforts at finding an intersection that literally had five corners were for naught. It wasn’t that they didn’t exist (which they do in abundance in NYC), or that I failed to find them (I found them all, thanks to the trusty Hagstrom’s Five Borough Atlas). It was rather that this particular neighborhood simply didn’t have such an intersection. What it did have was some great views of the bridge, little period row houses and a lot of character, making it suitable for a film set in 1964.

The first day of shooting was certainly one of the most difficult and harrowing I have ever had to endure in my career in film (although not quite as hair-raising as day one on EvenHand). It started relatively smoothly at a great location in Inwood (upper Manhattan): an old abandoned police precinct. With a little help from the production designer (Adrianne something-or-other), it had been transformed back into a pretty good facsimile of a ca. 1960’s precinct. It was the second location of the day that caused all the trouble.

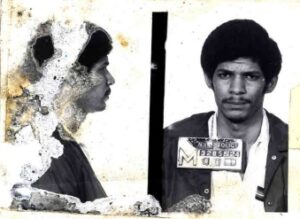

One of several mugshots I found at the abandoned precinct

I was on set, making sure that things were going smoothly from a locations standpoint, when a PA came up to me and said that the police were threatening to arrest our scenic artists at the next location, a subway entrance on 190th Street. I immediately got in the Batmobile (A shit-brown Dodge Omni Rent-a-Wreck with a giant Batman logo on the door that served as my mobile office) and raced to 190th Street.

Once there, I met with a Transit Police Officer who said that he was going to charge our scenic artists with defacing Transit Authority property. Ironically, they were actually repainting the station to get rid of the graffiti, a staple of the NYC Subway system at the time. I said, surely there is some mistake. We have permission to film here. I dug out my files and showed the permit from the NYC Mayor’s Office. He hemmed and hawed and said he had to get his lieutenant. The lieutenant arrived and scrutinized my paperwork. He said while it was all well and good to have the Mayor’s Office permit, we were missing the permit from the MTA. He had me there. I desperately tried to call the representative of the MTA’s Public Relations Dept. that I had dealt with, but she was on vacation that week. While I had certainly secured her permission to film there, she had evidently not processed it to the point where we had an actual permit. Not good.

By this time, a few departments from the shooting crew began to arrive. Things were wrapping up at location #1. The Lieutenant announced that he had better get the Captain down to see what was happening. By the time the Captain arrived, the entire crew was at the Subway station, waiting for me to secure permission for us to film there. The scenic artists had also not been able to complete their fine work. The pressure was mounting.

The Captain listened to my story, not unsympathetically, but there was a certain level of back-up with which I was not providing him. Unless I pulled something out of my hat, we were all going home — and I was probably going to be fired halfway through my first day on set. Sweating profusely by this time, especially as the line producer was hovering in an extremely agitated fashion, I rifled through my paperwork one more time. Finally, I found the key: an insurance certificate, naming the MTA as a named insured and specifying the 190th Street Subway station as one of the locations. This document finally satisfied the Transit Police, and the crew was given the go-ahead to film.

It was only the following week that the MTA became aware of what I knew as we were standing there on the street: the insurance certificate was not valid until several days later. I got my ass chewed out by them, but by then it didn’t matter. As I stood there sweating bullets, I helpfully pointed to the termination date, distracting from the fact that the certificate was in fact not yet in force.

I learned two valuable lessons that day. The first was to check and double check: the most important ingredients in covering your own ass. The second was: when failing the first, wing it.

– Joseph Pierson